What Is an ER Diagram? Beginner's Guide

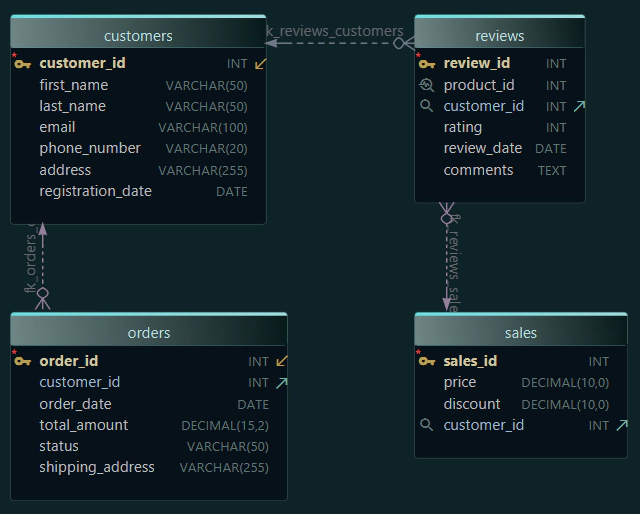

An Entity–Relationship diagram (ER diagram, ERD) is a visual representation of a database schema.

Its purpose is to see what’s in your database, how things link together, and where new data belongs.

What you need to know first

-

Entity (table) - An entity is something you store data about. In a relational database it becomes a table.

-

Attribute (column) - An attribute is a detail of an entity.

-

Primary key (PK) - A column (or set of columns) that uniquely identifies a row in a table. Each table should have one primary key.

-

Foreign key (FK) - A column that points to the primary key of another table - Foreign keys are relationships.

You don’t need to learn every symbol on day one. Focus on boxes (tables), keys, and the lines between them.

Why Use ER Diagrams?

Think of an ER diagram as a small map of your database. Instead of reading each table definition one by one, you can look at the picture to see what exists and how it connects.

Common reasons to use them:

- Plan a database design before writing SQL.

- Understand an existing schema when you join a project.

- Explain the structure to teammates, analysts, or students in a clear, visual way.

- Spot issues early, such as missing primary/foreign keys, duplicated data, or unclear names.

- Document the system so changes can be discussed and tracked over time.

Example: A small library

We store books and authors.

- Books →

book_id,title,published_year - Authors →

author_id,name - BookAuthors → connects books and authors

Why the extra table?

Because a book can have more than one author, and an author can write more than one book.

That is a many-to-many relationship, implemented by the link table BookAuthors.

From SQL Code to ER Diagram

An ER diagram is simply a visual form of the same information you define in SQL.

For example, the Employees table can be written as code on the left side, and you can see it visually in a diagram on the right side.

How to Build an ER Diagram

Whether you are working with PostgreSQL, MySQL, or another database, the steps are the same:

- Identify entities (the main tables, like Books or Authors).

- List attributes (columns inside each table).

- Choose primary keys (unique identifiers).

- Draw relationships (lines for one-to-many or many-to-many).

You can do this on paper, with a whiteboard, or with a schema tool that draws the diagram automatically.

Learn more about this from our articles:

- Learn how to design a relational schema ->

- See logical design basics ->

From Paper to Modern Tools

ER diagrams were once drawn on paper or whiteboards. That was fine for planning, but keeping drawings and the real database in sync was hard.

Today, schema tools make this easier:

- Draw first, SQL later. You create tables and foreign keys visually; the tool generates the

CREATE TABLEandALTER TABLEstatements behind the scenes. - Or start from SQL. Paste your

CREATE TABLEstatements (or connect to a database), and the tool parses them into a diagram automatically (reverse engineering). - Keep them in sync. When the model changes, you can update the database; when the database changes, you can refresh the model. Differences are highlighted.

- Set constraints visually. Primary keys, foreign keys,

NOT NULL, andUNIQUEcan be toggled in the diagram; the tool updates the SQL. - Document and share. Export diagrams or interactive docs so others can understand the structure without reading the SQL.

What this means for beginners: You can learn ER diagrams without writing much SQL at first. Still, knowing the basics—what a primary key and foreign key are—will help you read the diagram and check that the generated SQL matches your intent.

In our library example, you can either draw Books, Authors, and the link table BookAuthors and let the tool write the SQL, or paste the SQL and let the tool draw the three boxes and their connections for you.

Conclusion

An ER diagram is a simple picture of your schema. Start by finding tables, primary keys, and the lines between them.

With one solid example (Books–Authors–BookAuthors), you already understand the essentials.